Driving down many side streets and roads near the water in the Barnegat Bay Watershed, people may come across some now familiar signs:

Terrapins are an important part of the Barnegat Bay ecosystem. But what are they exactly? Why are they important to our environment? And what can members of our community do to ensure that terrapins and their habitat are protected?

The group of animals referred to as terrapins are a variety of small turtles that live in either fresh or brackish water. The species of terrapin local to the eastern United States is the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin), a brackish water species. There are seven subspecies of diamondback terrapin. The local subspecies is the northern diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin terrapin).

Diamondback terrapins are named for the diamond-shaped pattern on their carapace, or upper shell. They are easily identified by their distinctive light-colored body with darker splotches; the coloration can vary, however, from yellow to white to gray to tan. Diamondback terrapins have webbed feet, which help them to swim in estuarine environments. Mature females are larger than male terrapins, with females growing to an average of seven to nine inches, and males growing to about five inches in length. The females are so much larger because they must be able to carry their eggs. This distinctive difference between male and female individuals in a species is known as sexual dimorphism.

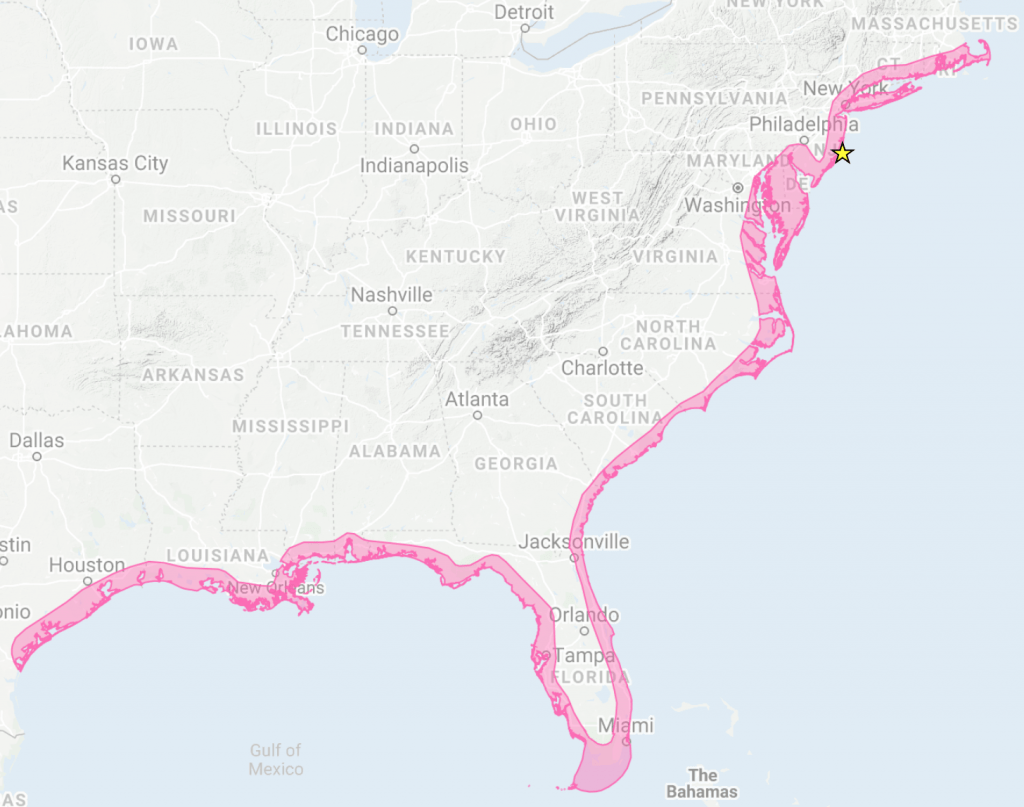

Diamondback terrapins are native along the east coast of the United States, as far north as Cape Cod and as far south as the Florida Keys; their range extends west through the Gulf of Mexico to Texas. There is even a population in Bermuda! Our local subspecies, the northern diamondback terrapin, is the northernmost subspecies.

Diamondback terrapins live in brackish environments, including salt marshes, tidal creeks, and estuaries. Their webbed feet make them strong swimmers, and they can survive in varying salinities due to their skin being largely impermeable to salt and due to their lachrymal salt glands, which help to remove excess salt from the body. Diamondback terrapins have a varied diet that includes fish, marine snails, crabs, mollusks, clams, worms, and carrion.

Diamondback terrapins were once abundant in the Barnegat Bay and along the east coast of the US. However, from the mid-1800s through to the 1920s, terrapins were harvested for turtle soup, once considered a delicacy. This led to their decline across their range, and their near extinction in some areas. However, the eventual decline in popularity of turtle soup, often attributed to prohibition banning sherry (an essential ingredient in the dish), allowed the terrapin population to recover.

In recent years, it has been suggested that northern diamondback terrapins could be an important indicator species for the health of Barnegat Bay and their salt marsh habitat. In 2010, a study by researchers at Drexel University found that tissues from northern diamondback terrapins in Barnegat Bay could be used as an indicator of persistent organic pollutants, such as certain pesticides.

Terrapins are not only important because of their ability to help scientists better understand estuarine ecosystems, but they are also important because their continued presence helps to promote local diversity and maintain a healthy estuarine ecosystem.

However, diamondback terrapins have been recognized as a vulnerable species by the IUCN Red List, and they are considered a species of special concern in the state of New Jersey due to evidence of decline. Human activity threatens the wellbeing of native terrapins.

One threat to terrapins is development along shorelines, such as the rapid development Ocean County has seen in recent decades. This has caused a decrease in nesting habitat, which forces female terrapins to lay their eggs in less than ideal conditions, such as less sandy soils that risk damaging the eggs. It can also force female terrapins to cross busy roads in search of ideal nesting ground, resulting in road mortalities. If you see a terrapin crossing the road, stop, and either wait for it to pass, or move it to the side of the road it was walking toward.

Similarly, climate change and sea level rise threaten northern diamondback terrapins. As sea level rises, storm surge heights and flood levels will increase, which can cause major damage to low-lying marsh habitat. Sea level rise and increased storm intensity will also cause erosion of terrapin habitat and nesting grounds.

Additional threats to terrapins are crab traps and abandoned fishing gear. Terrapins may enter traps in search of food and not be able to escape, resulting in them drowning. To prevent this, crabbers can attach bycatch reduction devices, or BRDs, to their traps, which prevent terrapins from entering any traps they are too large to escape. Crabbers can also work to ensure that they do not abandon their gear, which may become hazards to terrapins and other wildlife.

Although the consumption of terrapins is no longer common in the United States, wild populations of terrapins are still under threat from harvesting, specifically for the pet trade and foreign markets. For years, environmental groups petitioned the New Jersey state government to remove terrapins from the game species list, especially because those collecting terrapins for the pet trade could use their designation as a game species to justify their collecting of the turtles, even though keeping terrapins as pets is illegal. In 2016, NJ State Law S-1625 was passed, which designated the diamondback terrapin as a nongame indigenous species. This made it so harvesting of terrapins in New Jersey, both for the pet trade and consumption, is no longer legal.

Although S-1625 was passed, the effects of the illegal pet trade on terrapin populations in NJ can still be felt. For example, Dr. John Wnek, the research coordinator of Project Terrapin, explained that there was a local female terrapin that was taken illegally from our state and transported as part of the pet trade. She was marked in 2008 and recaptured in 2013, but then disappeared from any sort of record in NJ. Last year, she was found in Maine, and after being identified she was brought back to New Jersey and now lives at the Island Beach State Park Nature Center under the name Bayley, which was decided by a public contest.

Because Bayley was kept in captivity, it is unknown if she can be safely released back into the wild. According to Dr. Wnek, there are three main questions that must be answered before Bayley can be released: One, was she bred in captivity? The team is waiting until after the breeding season to consider releasing Bayley to make sure she was not fertilized. Two, does she carry any disease or blood-borne pathogen that could affect the natural population of terrapins? And three, can she even survive in the wild after being held in captivity?

Another project being undertaken by Project Terrapin is their turtle garden program. Turtle gardens are patches of sandy soil above the high-water line that can be used as safe, non-flood prone nesting habitat for female terrapins. Project Terrapin works with local organizations and homeowners to create these nesting spaces on their property to promote the safe nesting and hatching of terrapins locally. The organization also works to install terrapin crossing road signs near waterways to alert drivers that nesting females may be nearby and reduce road mortality.

To promote the importance of these turtles to the public, Project Terrapin is hosting an online Terrapin Appreciation Week from June 16-23, 2020. Highlights from their programming include children’s stories, Save Barnegat Bay research presentations, and a terrapin hatchling release.

Northern diamondback terrapins are an essential part of the Barnegat Bay ecosystem, and their continued wellbeing hinges on local communities working to protect them and preserve their habitat. By using BRDs while crabbing, watching for terrapins on the road, and educating others, we can all work to safeguard this local treasure.